It recently occurred to me that I was literally born to celebrate Christmas in the traditional order. What do I mean? Well, let me start with the order. These days, the Christmas season starts sometime in November. I suppose at this point, you'd have to say the "traditional" start is black Friday. Curmudgeons grumble when decorations and piped-in Christmas carols appear before Thanksgiving. The proper start is to haul out the decorations the weekend after, get a live tree if that's your thing, and start shopping, baking, etc. It's the season of church and office parties, all leading up to the main event on December 25. Once the presents are opened, food is packed away, and guests have gone home, it's time to take down the decorations. If you're especially lazy or busy traveling, you might let things go until New Year's.

But it wasn't always that way. We still sing about 12 days of Christmas. Some of us might even have a vague awareness of the Twelfth Night--either as a Shakespearean title or as a geeky excuse to drag out the Renaissance Fair costumes in winter. But what does it mean? 12 days, staring from December 25; that takes you to January 5. Why? Because Epiphany (Theophany in the East) falls on January 6--the next big feast on the calendar ends the Christmas season. Note: the traditional season does not end but starts on December 25. Formally, it ends at Epiphany, but in some places the celebration can actually extend into February.

Traditionally, the season before Christmas Day was Advent--the preparation for the feast. Instead of a month of lesser parties, Christmas songs, and shopping, you had 40 days of fasting, prayer, and almsgiving. It was a preparation of the heart for the feast. This is still a common observance among Eastern Orthodox. Among Western Christians, there is sometimes the positive spiritual preparation of the Advent Wreath. I've even spoken with at least one person who knew about an ascetic pre-Christmas season that might preclude listening to Christmas music. I don't think he was Orthodox--perhaps there are vestiges in Roman Catholic practice as well.

But generally speaking, the greatest hardship of the Advent Fast these days is how it runs counter to what everyone else is doing. For a month leading up to Christmas, you must politely abstain from offered foods or other aspects of our culture's pre-celebration. Then, the day finally arrives, and once again you're out of sync. You're finally ready to celebrate, but everyone else wants to put away the decorations and move on to something else.

Fortunately, there is New Year's Eve, which we can all celebrate together. (Apologies--and sympathy--to those of you still following the Julian calendar.) But aside from that, it's hard--especially for an introvert like me--to keep the celebration going on my own. Having visiting family helps--you retain something of a festive atmosphere just because you're together with those you don't see often.

But the point of all this is that my birthday also helps. I was born on the sixth day of Christmas, so I get the advantage of an extra excuse to celebrate. This realization not only encourages me in my feeble attempts to do something with the season; it's also a positive spin on something I've long lamented--the fact that my birthday comes so close to Christmas. And I'm happy to sacrifice December 30 as "my day," if it contributes to his.

Monday, December 27, 2010

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

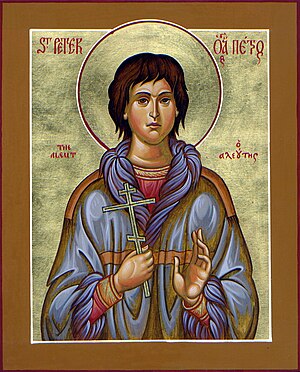

sources on St. Peter

Peter the Aleut is perhaps the most obscure Orthodox saint associated with North America. Very little is known about him, except the account of his martyrdom. And even that is a bit fuzzy, having originated with the testimony of one eyewitness, and recorded in a handful of written reports.

Unfortunately, the transcript of the 1819 eyewitness testimony does not appear to have made it into English yet. It is supposed to have been published in the first volume of the Russian collection Russia in California (ed. by J. Gibson, A. Istomin, V. Tishkov; 2005), with a planned English translation to follow. But I can't find any indication that the English translation has appeared, and since I don't read Russian, it wouldn't do me any good to track down a copy of the original.

A copy of his testimony is said to have been included with the earliest formal report, sent back to St. Petersburg in 1820 by Simeon Ivanovich Yanovsky, chief manager of the Russian Colonies from 1818 to 1820. It would appear that the written testimony was in fact included, since the administrator of the Russian American Company sent a much longer account to Tsar Alexander I later that year. Yanovsky, who eventually became a monk, wrote 45 years later in a letter to Igumen Damascene of Valaam Monastery about his relating the event to St. Herman. It is this last account that is usually repeated in lives of St. Peter.

Yanovsky's 1865 letter is a logical choice for this purpose, not only because it feels more hagiographical than the other accounts, but also because it cites St. Herman himself acknowledging Peter's sainthood. From a historical standpoint, this endorsement may not mean much, but his reaction of simple faith can serve as an example for the rest of us.

Both of Yanovsky's letters are reproduced in The Russian Orthodox Religious Mission in America, 1794-1837. His superior's longer report was published a decade later, in The Russian-American Colonies, To Siberia and Russian America: Three Centuries of Russian Eastward Expansion. All three are quoted in an article by Raymond A. Bucko, S.J., which is helpfully available online, though quite negatively slanted.

A special problem with Peter's martyrdom is identifying the actual location. Both of the 1820 reports indicate that the hunting party was taken captive somewhere on the Bay of San Pedro in 1815, and the eyewitness returned and gave his testimony in 1819. There is no evidence of a mission at San Pedro, so they may have been taken 30 miles north to San Gabriel. From here we're told that most of the party was taken 100 miles west to Santa Barbara, but that only two were placed in prison. It is unclear whether this means they were left imprisoned at the original mission, or were taken on to Santa Barbara with the others and imprisoned there. The former scenario seems more likely, since we're told the eyewitness was taken to Santa Barbara after Peter's death.

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

singin' "this'll be the day that I die"

I guess I'm what you would call a historical drinker. I have no inclination to get drunk. I don't drink because I'm in any particular mood. I don't have much of a taste for many types of alcohol. I only drink socially sometimes. But most of my significant motivators have been historical.

In Akkadian class we learned about how Mesopotamia and Egypt were beer cultures, while Palestine was a wine culture. We read an article about how someone actually followed an ancient Sumerian recipe to brew a modern equivalent, and I remember thinking that it would be interesting to sample.

Sometime later, I was exploring Christmas traditions--actually trying to give more meaning to the season--and got interested in wassail. I never did come up with a good recipe, but I gave it a shot--that might be the first beer I ever bought. (Well, I think Julie bought it, but at my request.)

I reacted to the low-carb craze with indignation. Bread in one form or another has been a staple of just about every culture on earth. For most of human history, meat was too expensive to eat very often. I wanted nothing to do with a diet plan that reversed this trend. Drinking beer (liquid bread) was one form of rebellion.

More recently, I was looking up the differences between types of spirits out of curiosity. (Yes, that's what a serious drinker I am--three months ago, I couldn't have told you the difference between bourbon and brandy.) I noticed that several were tied to specific locales--bourbon to Kentucky, vodka to Russia, and of course scotch. I began to wonder--was there a spirit indigenous to Maryland?

Well, as it turns out, there is--or was. Before Prohibition, there were two main variants of American rye whiskey--Pennsylvania and Maryland. There was a minor revival of the industry after the ban was lifted, but over the next few decades labels went under or were sold off. Eventually, rye production--what remained of it--moved entirely to Kentucky. As it happens, the Pennsylvania variety survived almost exclusively. To my knowledge, the last rye to be produced in Maryland, and the only authentic Maryland style rye being distilled today, is Pikesville.

Yes, "rye" is an actual drink, not just a delicious kind of bread. It makes a good deal more sense, now that I know what "them good old boys were drinking" with their whiskey in "American Pie" (the song, not the film). And appropriate, too, that the drink is featured in a song about death and memories. The Free State, where Governor Ritchie thumbed his nose at Prohibition, now has some of the toughest liquor laws in the Union and trucks its favorite drinks from elsewhere.

Yes, "rye" is an actual drink, not just a delicious kind of bread. It makes a good deal more sense, now that I know what "them good old boys were drinking" with their whiskey in "American Pie" (the song, not the film). And appropriate, too, that the drink is featured in a song about death and memories. The Free State, where Governor Ritchie thumbed his nose at Prohibition, now has some of the toughest liquor laws in the Union and trucks its favorite drinks from elsewhere.

Anyway, lucky for me the stuff is cheap. At $13, it wasn't too big a risk to buy a bottle and give it a try. (And speaking of cheap, I've already figured out that, matched drink for drink, it's a good deal more economical than beer.) So, how has it gone?

What? Diageo makes alcohol? Well, yes. As a matter of fact, they make Smirnoff, Johnnie Walker, Baileys, J&B, Captain Morgan, . . . they make a lot. But the reason for my double-take is that there's a Diageo plant just up Rt. 1, on the other side of the river in Relay. I've driven by it countless times--on the way to church, on the way to Walmart, on the way to get pit beef, etc. Pretty much everything around here sends you up or down Rt. 1, so odds are pretty good I'm going past the Diageo plant. I had no idea what they did.

What? Diageo makes alcohol? Well, yes. As a matter of fact, they make Smirnoff, Johnnie Walker, Baileys, J&B, Captain Morgan, . . . they make a lot. But the reason for my double-take is that there's a Diageo plant just up Rt. 1, on the other side of the river in Relay. I've driven by it countless times--on the way to church, on the way to Walmart, on the way to get pit beef, etc. Pretty much everything around here sends you up or down Rt. 1, so odds are pretty good I'm going past the Diageo plant. I had no idea what they did.

I put up a comment on Facebook, and a friend who grew up in the area says it used to smell like whiskey driving Rt. 1 through Relay. Apparently it was once Maryland's largest distillery (including rye), back when it looked something like this:

After Prohibition, Seagram's bought Calvert Distilling Company. Diageo bought Seagram's somewhere around 2000, but before that happened, the distilling operation in Relay shut down. I haven't discovered exactly what they do there now--distribution, and probably bottling? It doesn't smell like whiskey anymore, so I assume they're not distilling. They do, however, turn up here and there in lists of environmental violations, including something about radioactive materials--no idea what that is.

After Prohibition, Seagram's bought Calvert Distilling Company. Diageo bought Seagram's somewhere around 2000, but before that happened, the distilling operation in Relay shut down. I haven't discovered exactly what they do there now--distribution, and probably bottling? It doesn't smell like whiskey anymore, so I assume they're not distilling. They do, however, turn up here and there in lists of environmental violations, including something about radioactive materials--no idea what that is.

From Maryland rye to miscellaneous alcohol--the story of a state, the story of a town. Sometimes being a localist is just depressing.

In Akkadian class we learned about how Mesopotamia and Egypt were beer cultures, while Palestine was a wine culture. We read an article about how someone actually followed an ancient Sumerian recipe to brew a modern equivalent, and I remember thinking that it would be interesting to sample.

Sometime later, I was exploring Christmas traditions--actually trying to give more meaning to the season--and got interested in wassail. I never did come up with a good recipe, but I gave it a shot--that might be the first beer I ever bought. (Well, I think Julie bought it, but at my request.)

I reacted to the low-carb craze with indignation. Bread in one form or another has been a staple of just about every culture on earth. For most of human history, meat was too expensive to eat very often. I wanted nothing to do with a diet plan that reversed this trend. Drinking beer (liquid bread) was one form of rebellion.

More recently, I was looking up the differences between types of spirits out of curiosity. (Yes, that's what a serious drinker I am--three months ago, I couldn't have told you the difference between bourbon and brandy.) I noticed that several were tied to specific locales--bourbon to Kentucky, vodka to Russia, and of course scotch. I began to wonder--was there a spirit indigenous to Maryland?

Well, as it turns out, there is--or was. Before Prohibition, there were two main variants of American rye whiskey--Pennsylvania and Maryland. There was a minor revival of the industry after the ban was lifted, but over the next few decades labels went under or were sold off. Eventually, rye production--what remained of it--moved entirely to Kentucky. As it happens, the Pennsylvania variety survived almost exclusively. To my knowledge, the last rye to be produced in Maryland, and the only authentic Maryland style rye being distilled today, is Pikesville.

Yes, "rye" is an actual drink, not just a delicious kind of bread. It makes a good deal more sense, now that I know what "them good old boys were drinking" with their whiskey in "American Pie" (the song, not the film). And appropriate, too, that the drink is featured in a song about death and memories. The Free State, where Governor Ritchie thumbed his nose at Prohibition, now has some of the toughest liquor laws in the Union and trucks its favorite drinks from elsewhere.

Yes, "rye" is an actual drink, not just a delicious kind of bread. It makes a good deal more sense, now that I know what "them good old boys were drinking" with their whiskey in "American Pie" (the song, not the film). And appropriate, too, that the drink is featured in a song about death and memories. The Free State, where Governor Ritchie thumbed his nose at Prohibition, now has some of the toughest liquor laws in the Union and trucks its favorite drinks from elsewhere.Anyway, lucky for me the stuff is cheap. At $13, it wasn't too big a risk to buy a bottle and give it a try. (And speaking of cheap, I've already figured out that, matched drink for drink, it's a good deal more economical than beer.) So, how has it gone?

- I figured I ought to start by trying it more or less unadulterated. I wasn't quite ready to start pounding shots (don't even own a shot glass), so I had it on the rocks. I don't know enough of the terminology to say what I didn't like about it, but I decided pretty quickly that I'd need to mix it somehow.

- My next attempt was a rye sour. That looked pretty simple to make and didn't require any ingredients I didn't already have. Success. The concoction was much more palatable.

- I'd seen somewhere that rye was the traditional base for a Manhattan. I didn't have vermouth or bitters, and I didn't want to buy them before knowing what I was getting into, so I ordered one while we were out for dinner. Maybe Red Lobster just doesn't make a good Manhattan, but it tasted almost exactly like cough syrup. Guess I'll stick with the sour.

- I also ran across a description of a hot toddy, which is essentially a whiskey sour served hot. Tried one of those the other day--that wasn't too bad either. OK, so now I have a couple of options for using up the bottle.

What? Diageo makes alcohol? Well, yes. As a matter of fact, they make Smirnoff, Johnnie Walker, Baileys, J&B, Captain Morgan, . . . they make a lot. But the reason for my double-take is that there's a Diageo plant just up Rt. 1, on the other side of the river in Relay. I've driven by it countless times--on the way to church, on the way to Walmart, on the way to get pit beef, etc. Pretty much everything around here sends you up or down Rt. 1, so odds are pretty good I'm going past the Diageo plant. I had no idea what they did.

What? Diageo makes alcohol? Well, yes. As a matter of fact, they make Smirnoff, Johnnie Walker, Baileys, J&B, Captain Morgan, . . . they make a lot. But the reason for my double-take is that there's a Diageo plant just up Rt. 1, on the other side of the river in Relay. I've driven by it countless times--on the way to church, on the way to Walmart, on the way to get pit beef, etc. Pretty much everything around here sends you up or down Rt. 1, so odds are pretty good I'm going past the Diageo plant. I had no idea what they did.I put up a comment on Facebook, and a friend who grew up in the area says it used to smell like whiskey driving Rt. 1 through Relay. Apparently it was once Maryland's largest distillery (including rye), back when it looked something like this:

After Prohibition, Seagram's bought Calvert Distilling Company. Diageo bought Seagram's somewhere around 2000, but before that happened, the distilling operation in Relay shut down. I haven't discovered exactly what they do there now--distribution, and probably bottling? It doesn't smell like whiskey anymore, so I assume they're not distilling. They do, however, turn up here and there in lists of environmental violations, including something about radioactive materials--no idea what that is.

After Prohibition, Seagram's bought Calvert Distilling Company. Diageo bought Seagram's somewhere around 2000, but before that happened, the distilling operation in Relay shut down. I haven't discovered exactly what they do there now--distribution, and probably bottling? It doesn't smell like whiskey anymore, so I assume they're not distilling. They do, however, turn up here and there in lists of environmental violations, including something about radioactive materials--no idea what that is.From Maryland rye to miscellaneous alcohol--the story of a state, the story of a town. Sometimes being a localist is just depressing.

Thursday, November 25, 2010

Thanksgiving

Our parish observes this American holiday at Wednesday compline by singing the Akathist of Thanksgiving. It's not what you might think. Although the Akathist was composed quite recently, it had nothing to do with Pilgrims and sweet potatoes. The hymn is attributed to a priest Gregory Petrov and is said to have been discovered after his death in a Soviet prison camp. I liken it to the Mourner's Kaddish in Jewish tradition, which is recited by those who have recently lost a loved one. The prayer itself seems to have nothing to do with mourning but is rather a beautiful praise to God. Similarly, the Akathist was apparently written amid intense suffering, but its focus is praise for God's manifold goodness. In both cases, the message seems to be that our greatest need to offer praise and thanksgiving is when things aren't going so well--when the only alternative is to slander God for his silence, laziness, or capricious violence.

Still, if we need such expressions most when life is at its worst, that hardly means they can't apply as well in less dire circumstances. So I think it's a good meditation for Thanksgiving Day and probably for the rest of the year. I actually went through the hymn not long ago to pull out some lines that might be useful to memorize for various occasions. In some Jewish prayer books there is a section of short blessings to be said in situations that might come up as we go through our daily lives. I thought it would be nice to have something comparable to work with, though admittedly I haven't thought much about it since.

Anyway, here's the list I came up with. (Certainly there could be others.) A few bracketed items were actually drawn from other blessings, but most of what's here is from the Akathist.

Still, if we need such expressions most when life is at its worst, that hardly means they can't apply as well in less dire circumstances. So I think it's a good meditation for Thanksgiving Day and probably for the rest of the year. I actually went through the hymn not long ago to pull out some lines that might be useful to memorize for various occasions. In some Jewish prayer books there is a section of short blessings to be said in situations that might come up as we go through our daily lives. I thought it would be nice to have something comparable to work with, though admittedly I haven't thought much about it since.

Anyway, here's the list I came up with. (Certainly there could be others.) A few bracketed items were actually drawn from other blessings, but most of what's here is from the Akathist.

Food

- Feast: Glory to Thee for the feast of life!

- [Bread: Glory to Thee, who didst bless the five loaves and didst therewith feed the five thousand!

- Meat: Glory to Thee, who didst command the fatted calf to be slain for thy son who had gone astray, and who had returned again to Thee!]

- Fruit: Glory to Thee for the delightful diversities of berries and of fruits!

- [Wine: Glory to Thee, who permittest the fruit of the vine to come to maturity!

- Other: Glory to Thee, the Creator and Maker of all things!]

Fragrance

- Flowers: Glory to Thee for the perfume of lilies-of-the-valley and of roses!

- Other: Glory to Thee Who hast brought forth from the earth’s darkness diverse colours, taste, and fragrance!

Daily Cycle

- Morning: Glory to Thee for the diamond brilliance of morning dew!

- Sunrise: Glory to Thee for the smile of light awakening!

- Meditation: Glory to Thee for the happiness of living, moving, and meditating!

- Manual Labor: Glory to Thee for the vivifying power of labour!

- Service: Glory to Thee, Who transfigurest our life by good deeds!

- Reward for Service: Glory to Thee, Who dost vouchsafe great rewards for precious good deeds!

- Sunset: Glory to Thee for the farewell rays of the setting sun!

- Evening: Glory to Thee in the tender hour of evening!

- Night: Glory to Thee for Thy favour in the darkness, when all the world is distant!

- Sleep: Glory to Thee for the rest of grace-filled sleep!

Encounters

- Family/Friends: Glory to Thee for the love of kindred, and the faithfulness of friends!

- Catechumen: Glory to Thee Who hast founded Thy Church as a quiet refuge for a spent world!

- Newly Illumined: Glory to Thee Who renewest us by the life-giving waters of baptism!

- Secular Thinker: Glory to Thee for the genius of the human mind!

- Scripture/Saint: Glory to Thee for the fiery tongues of inspiration!

- Other People: Glory to Thee for providential meetings with people!

- Domestic Animals: Glory to Thee for the meekness of animals which serve me!

- Wild Animals: Glory to Thee, for the thousands of Thy creatures Thou hast set round about us!

- Nature: Glory to Thee Who hast revealed unto me the beauty of the universe!

- Science: Glory to Thee Who hast shown Thine unfathomable power in the laws of the universe!

- Revelation: Glory to Thee for all that Thou hast revealed unto us by Thy goodness!

- Mystery: Glory to Thee for all that Thou hast concealed in Thy wisdom!

- Grief: Glory to Thee, Who sendest failures and sorrows, that we might pity the sufferings of others!

- Passage of Grief: Glory to Thee Who curest sorrows and bereavements with the healing passage of time!

- Confession: Glory to Thee, Who restorest to penitents purity as a spotless lily!

- Providence: Glory to Thee for providential coincidence of circumstances!

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

Who I'm voting for and why

Election Day is coming, and I've been trying to sort out my votes. I present my choices and reasons here mostly for entertainment value. I don't consider myself a model voter, but my shortcomings are probably normal. I don't pay nearly enough attention to the specifics of what's going on in government. The election rolls around, and I don't even know whether I like the job most of the incumbents are doing or not (and those on whom I have an opinion, it's probably not for very good reasons), let alone what their challengers have to offer. I do what I can to inform myself--I watch the forums sponsored by the League of Women Voters, look at the candidates' Web sites, and try to pay attention if I see anything relevant in the local news. But in the end I'm probably just as bad a judge as anyone else of who should be elected. It's part of the reason that I lean monarchist, but when the day arrives, I still feel like I ought to vote. I may not have much idea why, but I want it to be something better than randomly punching the screen, or voting a party line.

Here, then, are my choices as they stand right now. I might still change my mind before the day arrives:

Governor: Eric Delano Knowles (C). Last time around, I voted for O'Malley. It seemed to me that Ehrlich couldn't speak for five minutes without promoting the legalization of slot machines in MD. He was (and probably still is) the rare Republican candidate who could win in MD--fine. But if he's going to make state-run moral corruption his thing, I'd rather have a bleeding-heart liberal. O'Malley wasn't any better, so I'm going with a third party. I can't really get on board with the Libertarian candidate's scheme to sell the Bay, and if I'm voting conservative I'd rather have someone who's pro-life. Knowles just seems like a better fit to my ideals. Not that I think any third-party candidate has a serious chance of winning, but I live by the assumption that I'm throwing away my vote one way or another. May as well do it with a clean conscience.

U. S. Senator: Eric Wargotz (R). I've never been a fan of the Mik. I'm not voting for him--I'm voting against her. Besides, Wargotz is just a cool name.

Congressional Representative: Jerry McKinley (L). I don't care much for Sarbanes either. He's Greek Orthodox, but sorry--that doesn't seem to make him a good representative of my views. He voted for TARP, which got him on my bad side, and I haven't seen anything to change my opinion since then. I was going to vote for the Republican candidate (who probably can't beat him anyway), but in the LWV forum he came across as angry and hypocritical. He kept attacking Sarbanes for being a lawyer, a career politician, and the son of a career politician. But his idea of bringing in someone from the private sector is a guy who went from the military to defense contracting. Nice try. McKinley had similar views on the issues but sounded a lot more comfortable and level-headed.

State Senator: Edward J. Kasemeyer (D). I've had a few opportunities to hear Kasemeyer answer questions, and he seems to have his head screwed on right. I don't follow state politics all that closely, so I don't have much to go by, but I haven't had occasion to object to any stance he's taken. The Republican candidate, as with the guy running for Congress, is just way too emotional. I dunno--maybe it's the Tea Party thing. Do Republicans think they have to seem perpetually outraged to show they're hip with the times?

State Delegates: James E. Malone Jr. (D) and Joe Hooe (R). This one was a tough call. For those who don't know, we elect two delegates in our sub-district, and my inclination is to go with both parties for the sake of balance. I didn't find much about Hooe's views that I disliked, and he doesn't try to paint himself (at least, not on his Web site) as a big Ehrlich supporter. Plus, he has a cool name and a slogan to go with it. It was kind of a toss-up for me between the incumbents, but I do like Malone's constituent service. If both my picks got elected, at least they'd have in common their love for rhymes.

County Executive: Ken Ulman (D). As far as I can tell, Ulman has done a decent job. In any case, I'm not convinced of the Republicans' argument, that the current budget situation is mostly due to the poor management of the Democrats. We've obviously had a bad economy to deal with over the past few years, and we're doing a lot better than many local governments.

County Council: Courtney Watson (D). Possibly the only candidate I have a serious opinion about is Councilwoman Watson. I've tried to follow the actions of the council, and in general, I've been impressed both with her competence as Council Chair and with her thinking on issues. She's been responsive when I've contacted her about concerns, she seems to have a good understanding of what's important to her constituents, and her politics are generally balanced between left and right. I can only laugh when the Republican candidate accuses her of being a tax-and-spend liberal and part of the entrenched Democratic control of the county.

Circuit Court Clerk: Jason Reddish (D). I read an article the other day about the races for Court Clerk and Register of Wills. Both offices are currently held by Republican women well beyond retirement age; both are being challenged by Democratic men in their 20s. The main reason I even have an opinion is that jobs are hard enough to find these days. I didn't get the impression that either of the incumbents really needs the income, so I favor giving the jobs to the younger challengers, who are of an age when they should be employed. Beyond that, the article mentioned that the Court Clerk's office is badly in need of automation, and if this guy has ideas for making that happen, I say, let him give it a shot.

Register of Wills: Byron Macfarlane (D). See above.

Board of Education: Robert D. Ballinger II, Leslie Kornreich, Brian Meshkin, and David E. Proudfoot. This is a difficult category for me. None of the candidates really stands out, and I'm supposed to vote for four of them. I don't care much for the two incumbents. Aquino seems too arrogant, and French is a Communist who wants to take children away from their parents and brainwash them 24/7. (I'm kidding--but I definitely disagree with her view that we need longer school days and fewer breaks. There are plenty of activities for students who want to (or whose parents want them to) spend all their time away from home, but for parents who still want time to educate their own children in skills and values that they won't get from public school, there needs to be a limit to institutionalization. Ballinger seems to care very genuinely, not only about doing a good job with our kids' education, but also about listening to the voters for their input. Kornreich's platform is far too narrow, but I'm not convinced she'd be worse than any of the others, and she is from Elkridge. Meshkin seems to have some decent ideas and experience on advisory committees for the school board in the past. Proudfoot works in education and seems to have a good handle on the issues. Plus, it's hard to resist the name.

Constitutional Convention: No. This seems to be a formality. The state constitution requires that they ask every 20 years whether we want a convention. Since I'm not at all convinced that we could craft a better constitution today, I say "no."

Jury Trial Amendment: No. The current limit on a civil trial to request a jury is $10k. The amendment would raise the limit to $15k. I don't have much to go on here, but since jury trials are a basic right in our society, I'd rather not see the minimum increase unless someone really convinces me it's necessary.

Baltimore Orphan's Court Amendment: No. Currently there is no requirement in the City of Baltimore that Orphan's Court judges be qualified lawyers. I would guess that in most cases people will probably vote for qualified lawyers anyway (assuming they know or care), but I like the idea of leaving it open to the will of the people.

There are several other offices on the ballot, most of them unopposed, which I'm not going to bother voting on if I know nothing about the candidate. Going forward, I want to pay more consistent attention to county government and school board issues. We have the cable channels--may as well make use of them. Maybe in another two-to-four years I'll be in a better position to make some of these choices. It wouldn't hurt to keep myself better informed about state politics either, though I'm not sure of the best way to do that. National politics really don't concern me much. By the time you get to that level, I have absolutely no hope that my opinion makes any difference anyway.

Here, then, are my choices as they stand right now. I might still change my mind before the day arrives:

Governor: Eric Delano Knowles (C). Last time around, I voted for O'Malley. It seemed to me that Ehrlich couldn't speak for five minutes without promoting the legalization of slot machines in MD. He was (and probably still is) the rare Republican candidate who could win in MD--fine. But if he's going to make state-run moral corruption his thing, I'd rather have a bleeding-heart liberal. O'Malley wasn't any better, so I'm going with a third party. I can't really get on board with the Libertarian candidate's scheme to sell the Bay, and if I'm voting conservative I'd rather have someone who's pro-life. Knowles just seems like a better fit to my ideals. Not that I think any third-party candidate has a serious chance of winning, but I live by the assumption that I'm throwing away my vote one way or another. May as well do it with a clean conscience.

U. S. Senator: Eric Wargotz (R). I've never been a fan of the Mik. I'm not voting for him--I'm voting against her. Besides, Wargotz is just a cool name.

Congressional Representative: Jerry McKinley (L). I don't care much for Sarbanes either. He's Greek Orthodox, but sorry--that doesn't seem to make him a good representative of my views. He voted for TARP, which got him on my bad side, and I haven't seen anything to change my opinion since then. I was going to vote for the Republican candidate (who probably can't beat him anyway), but in the LWV forum he came across as angry and hypocritical. He kept attacking Sarbanes for being a lawyer, a career politician, and the son of a career politician. But his idea of bringing in someone from the private sector is a guy who went from the military to defense contracting. Nice try. McKinley had similar views on the issues but sounded a lot more comfortable and level-headed.

State Senator: Edward J. Kasemeyer (D). I've had a few opportunities to hear Kasemeyer answer questions, and he seems to have his head screwed on right. I don't follow state politics all that closely, so I don't have much to go by, but I haven't had occasion to object to any stance he's taken. The Republican candidate, as with the guy running for Congress, is just way too emotional. I dunno--maybe it's the Tea Party thing. Do Republicans think they have to seem perpetually outraged to show they're hip with the times?

State Delegates: James E. Malone Jr. (D) and Joe Hooe (R). This one was a tough call. For those who don't know, we elect two delegates in our sub-district, and my inclination is to go with both parties for the sake of balance. I didn't find much about Hooe's views that I disliked, and he doesn't try to paint himself (at least, not on his Web site) as a big Ehrlich supporter. Plus, he has a cool name and a slogan to go with it. It was kind of a toss-up for me between the incumbents, but I do like Malone's constituent service. If both my picks got elected, at least they'd have in common their love for rhymes.

County Executive: Ken Ulman (D). As far as I can tell, Ulman has done a decent job. In any case, I'm not convinced of the Republicans' argument, that the current budget situation is mostly due to the poor management of the Democrats. We've obviously had a bad economy to deal with over the past few years, and we're doing a lot better than many local governments.

County Council: Courtney Watson (D). Possibly the only candidate I have a serious opinion about is Councilwoman Watson. I've tried to follow the actions of the council, and in general, I've been impressed both with her competence as Council Chair and with her thinking on issues. She's been responsive when I've contacted her about concerns, she seems to have a good understanding of what's important to her constituents, and her politics are generally balanced between left and right. I can only laugh when the Republican candidate accuses her of being a tax-and-spend liberal and part of the entrenched Democratic control of the county.

Circuit Court Clerk: Jason Reddish (D). I read an article the other day about the races for Court Clerk and Register of Wills. Both offices are currently held by Republican women well beyond retirement age; both are being challenged by Democratic men in their 20s. The main reason I even have an opinion is that jobs are hard enough to find these days. I didn't get the impression that either of the incumbents really needs the income, so I favor giving the jobs to the younger challengers, who are of an age when they should be employed. Beyond that, the article mentioned that the Court Clerk's office is badly in need of automation, and if this guy has ideas for making that happen, I say, let him give it a shot.

Register of Wills: Byron Macfarlane (D). See above.

Board of Education: Robert D. Ballinger II, Leslie Kornreich, Brian Meshkin, and David E. Proudfoot. This is a difficult category for me. None of the candidates really stands out, and I'm supposed to vote for four of them. I don't care much for the two incumbents. Aquino seems too arrogant, and French is a Communist who wants to take children away from their parents and brainwash them 24/7. (I'm kidding--but I definitely disagree with her view that we need longer school days and fewer breaks. There are plenty of activities for students who want to (or whose parents want them to) spend all their time away from home, but for parents who still want time to educate their own children in skills and values that they won't get from public school, there needs to be a limit to institutionalization. Ballinger seems to care very genuinely, not only about doing a good job with our kids' education, but also about listening to the voters for their input. Kornreich's platform is far too narrow, but I'm not convinced she'd be worse than any of the others, and she is from Elkridge. Meshkin seems to have some decent ideas and experience on advisory committees for the school board in the past. Proudfoot works in education and seems to have a good handle on the issues. Plus, it's hard to resist the name.

Constitutional Convention: No. This seems to be a formality. The state constitution requires that they ask every 20 years whether we want a convention. Since I'm not at all convinced that we could craft a better constitution today, I say "no."

Jury Trial Amendment: No. The current limit on a civil trial to request a jury is $10k. The amendment would raise the limit to $15k. I don't have much to go on here, but since jury trials are a basic right in our society, I'd rather not see the minimum increase unless someone really convinces me it's necessary.

Baltimore Orphan's Court Amendment: No. Currently there is no requirement in the City of Baltimore that Orphan's Court judges be qualified lawyers. I would guess that in most cases people will probably vote for qualified lawyers anyway (assuming they know or care), but I like the idea of leaving it open to the will of the people.

There are several other offices on the ballot, most of them unopposed, which I'm not going to bother voting on if I know nothing about the candidate. Going forward, I want to pay more consistent attention to county government and school board issues. We have the cable channels--may as well make use of them. Maybe in another two-to-four years I'll be in a better position to make some of these choices. It wouldn't hurt to keep myself better informed about state politics either, though I'm not sure of the best way to do that. National politics really don't concern me much. By the time you get to that level, I have absolutely no hope that my opinion makes any difference anyway.

Saturday, October 9, 2010

slowly getting the hang of this bike repair thing

For some reason, I've never done much in the way of working on stuff. I can change the oil in the car if I have to (since we don't have ramps, I usually don't), but I have to take it to a guy for pretty much everything else. We rented our entire adult life until two years ago, and then we bought a new house under warranty, so that hasn't generated much work either. One thing that riding a bike has done is get me fixing something.

I guess I looked at it as a fresh start. I'd never been a serious cyclist, so there was no reason I ought to have known how to work on one. Plus, part of my agenda in riding a bike is that it's a friendlier mode of transportation. It's cheap to operate, cheap to fix even if you do pay someone else to do the work, and relatively easy to learn to do it yourself. So, I'm learning--slowly, but surely.

I learned basic maintenance like greasing the chain and tightening the brakes early on. I think the first real repairs it needed were a bald back tire and a busted shifter cable. More recently, I've had several flat tires and botched almost as many patch jobs. (Maybe it's just not worth it, but the last one was on a brand new tube that I might have punctured while putting it in. I had to try.) One thing I'm getting really comfortable with is taking off the back wheel, which used to worry me. I was always concerned that I wouldn't know how to put it back on, but after so many times taking it on and off, I feel confident that I could change a back tire on the side of the road if I had to.

This time, in addition to the flat tire (which went flat again after the first three attempts), my chain broke the same day. I didn't have a chain tool, and I wasn't sure I'd know how to get the chain back on the rear derailer properly, so I figured this time I'd let the bike shop install it. It was only $10, and I had enough other stuff to deal with (on a weekend when I'm alone with the kids, no less), so I think it was worth it. It wouldn't shift properly afterward, so I had to figure out the adjustment on that (at least, I think I figured it out). Also, for some reason the rear brake was dragging, which wasn't hard to deal with.

I continue to discover advantages to owning a bike that's probably older than I am. ("Old school," I've heard it called more than once.) I went into the shop expecting to get a $35 10-speed chain. The guy looked at it and said, "Oh, you mean a 5-speed." He went and found a chain that cost half as much, which I guess more than covered the installation charge. Also, after reading online about the various adjustments that might or might not need to be made to address my shifting problem, I discovered that my derailer apparently only has one adjustment mechanism--a single screw that moves it closer to the wheel when you tighten it and further away when you loosen it. The shifting is by no means perfect (it never was), but it will hit all the gears now, so I guess it was a success. Maybe it would be possible to get a better fit with a newer, more complicated derailer. But at least I didn't have to figure one out at this point.

I suppose the drawback is that I'm learning how to fix an obsolete bike. If I ever do get a new one, will I have to learn bicycle repair all over again? It can also be tricky finding the parts that I need for it, and something as simple as mounting a water bottle rack becomes more complicated. At least no one seems interested in stealing it, which may be the best feature of all.

I guess I looked at it as a fresh start. I'd never been a serious cyclist, so there was no reason I ought to have known how to work on one. Plus, part of my agenda in riding a bike is that it's a friendlier mode of transportation. It's cheap to operate, cheap to fix even if you do pay someone else to do the work, and relatively easy to learn to do it yourself. So, I'm learning--slowly, but surely.

I learned basic maintenance like greasing the chain and tightening the brakes early on. I think the first real repairs it needed were a bald back tire and a busted shifter cable. More recently, I've had several flat tires and botched almost as many patch jobs. (Maybe it's just not worth it, but the last one was on a brand new tube that I might have punctured while putting it in. I had to try.) One thing I'm getting really comfortable with is taking off the back wheel, which used to worry me. I was always concerned that I wouldn't know how to put it back on, but after so many times taking it on and off, I feel confident that I could change a back tire on the side of the road if I had to.

This time, in addition to the flat tire (which went flat again after the first three attempts), my chain broke the same day. I didn't have a chain tool, and I wasn't sure I'd know how to get the chain back on the rear derailer properly, so I figured this time I'd let the bike shop install it. It was only $10, and I had enough other stuff to deal with (on a weekend when I'm alone with the kids, no less), so I think it was worth it. It wouldn't shift properly afterward, so I had to figure out the adjustment on that (at least, I think I figured it out). Also, for some reason the rear brake was dragging, which wasn't hard to deal with.

I continue to discover advantages to owning a bike that's probably older than I am. ("Old school," I've heard it called more than once.) I went into the shop expecting to get a $35 10-speed chain. The guy looked at it and said, "Oh, you mean a 5-speed." He went and found a chain that cost half as much, which I guess more than covered the installation charge. Also, after reading online about the various adjustments that might or might not need to be made to address my shifting problem, I discovered that my derailer apparently only has one adjustment mechanism--a single screw that moves it closer to the wheel when you tighten it and further away when you loosen it. The shifting is by no means perfect (it never was), but it will hit all the gears now, so I guess it was a success. Maybe it would be possible to get a better fit with a newer, more complicated derailer. But at least I didn't have to figure one out at this point.

I suppose the drawback is that I'm learning how to fix an obsolete bike. If I ever do get a new one, will I have to learn bicycle repair all over again? It can also be tricky finding the parts that I need for it, and something as simple as mounting a water bottle rack becomes more complicated. At least no one seems interested in stealing it, which may be the best feature of all.

Friday, October 1, 2010

the terrifying world of E. B. White

"You children be quiet till we get the pig unloaded," said Mrs. Arable.And that was the last time they ever saw those dear, sweet children . . . oh, wait. Here it is:

"Let's let the children go off by themselves," suggested Mr. Arable. "The Fair only comes once a year." Mr. Arable gave Fern two quarters and two dimes. He gave Avery five dimes and four nickels. "Now run along!" he said. "And remember, the money has to last all day. Don't spend it all the first few minutes. And be back here at the truck at noontime so we can all have lunch together. And don't eat a lot of stuff that's going to make you sick to your stomachs."

"And if you go in those swings," said Mrs. Arable, "you hang on tight! You hang on very tight. Hear me?"

"And don't get lost!" said Mrs. Zuckerman.

"And don't get dirty!"

"Don't get overheated!" said their mother.

"Watch out for pickpockets!" cautioned their father.

"And don't cross the race track when the horses are coming!" cried Mrs. Zuckerman.

The children grabbed each other by the hand and danced off in the direction of the merry-go-round, toward the wonderful music and the wonderful adventure and the wonderful excitement, into the wonderful midway where there would be no parents to guard them and guide them, and where they could be happy and free and do as they pleased. Mrs. Arable stood quietly and watched them go. Then she sighed. Then she blew her nose.

"Do you really think it's all right?" she asked.

"Well, they've got to grow up some time," said Mr. Arable. "And a fair is a good place to start, I guess."

At noon the Zuckermans and the Arables returned to the pigpen. Then, a few minutes later, Fern and Avery showed up. Fern had a monkey doll in her arms and was eating Crackerjack. Avery had a balloon tied to his ear and was chewing a candied apple. The children were hot and dirty.

Monday, August 30, 2010

Two Romanian Elders Discuss Salvation and God's Mercy

This dialog appeared in The Orthodox Word 272 (2010) 148-51. I'm hardly an expert, but it seems to me that it beautifully captures the complexity of Orthodox soteriology. There's always this tension between faith and humility, such that it's almost impossible to express without an apparent contradiction.

In 1996, two contemporary spiritual fathers, Fr. Teofil (Paraian) and Fr. Arsenie (Papacioc), met at Techirghiol Monastery in Romania. Fr. Arsenie was a spiritual son of Elder Cleopa (Ilie). He was imprisoned numerous times by the authorities, and at times lived in the wilderness to avoid further arrest. Although an ascetic himself, he is known for counsels on moderation, in combination with continual watchfulness. Today, at the age of 95, he continues to be the spiritual father at Techirghiol Women's Monastery. Fr. Teofil was a hieromonk at the Transylvanian monastery of Simbata de Sus. Born blind, he nevertheless completed his theological studies, learned three languages, and stuidied Patristic texts recorded on cassette tapes. He became one of the great luminaries of the Romanian Church in the twentieth century. He reposed on October 29, 2009, in the rank of archimandrite. Here is a part of that conversation:

Fr. T: Are you certain that all will be well for you in eternity?

Fr. A: I could not say that, most venerable Father! Please, believe me when I say, "I'm the only one who won't be saved!"

Fr. T: Do you believe so?

Fr. A: Yes, but I have great hope!

Fr. T: If you're hopeful, why do you express yourself like that?

Fr. A: The mind in hell and the hope in God! Without the grace of God, our deeds don't save us in any way.

Fr. T: Well . . . but it's impossible for God not to want to save us!

Fr. A: Yes, but I can't impose conditions on Him!

Fr. T: Well, without imposing conditions, God being Love . . .

Fr. A: Most venerable Father, I somehow in all honesty before a father confessor say: I will be saved because I suffered . . .

Fr. T: I honestly tell you that I have the certainty that I will go to the good, but not for my deeds!

Fr. A: I only hope!

Fr. T: Well, I can say that I have the certitude that if I hope . . .

Fr. A: This is not an Orthodox position!

Fr. T: Maybe I'm not Orthodox?

Fr. A: The truth is that our deeds don't save us in any way without God's mercy!

Fr. T: Do you know what I'll say to God when I'm standing in front of Him? Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner! I won't say anything else to Him!

Fr. A: I made myself a [burial] cross at Zamfira Monastery, where I confess to Fr. Gavril (Stoica), and this is what I wrote on the Cross: Jesus, Jesus, Jesus--forgive me!

Fr. T: I can't imagine God saying, "I don't want you," after I've lived with Him all of my life.

Fr. A: He loves us so much, and this gives me hope!

Fr. T: Father, if we count on God's mercy, we need not hesitate!

Fr. A: I don't want to count on God's mercy without considering our life and deeds. The salvation process involves not just the grace of God, but also our deeds. If only He could find us on the way. The struggle is to be on the way and to be honest with the fight!

Fr. T: I don't worry, because I have confidence in God's goodness!

Fr. A: I worry, but I'm also hopeful!

Fr. T: It's extraordinary when you say this, since God is our Father!

Fr. A: Yes, but I can't say that I have the certitude of salvation!

Fr. T: But why can't you say it?

Fr. A: If God allows me, I will say this on my deathbed: "God, I thank Thee that I die a monk!" But I have the thought that my deeds are leading me to hell. If God wants to save me, He can do it! But I can't say for sure that He will forgive me.

Fr. T: But I am sure that He forgives us!

Fr. A: I also have hope in the Lord! He even told St. Silouan, "Keep thy mind in hell and despair not!" The world does not yet know how much God loves us, how "passionately in love" with us God is!

Fr. T: You see how beautifully you say it.

Fr. A: But I can't say that I have certitude. Only the Protestants say that they have the surety of salvation. For our deeds don't save us without the grace of God; and the grace of God only comes if there is authentic humility. Can I say that I'm humble?

Saturday, June 26, 2010

the impermeable Shire

I'm not sure I have a favorite movie, but if forced to answer the question, I usually refer to the Lord of the Rings project (which is technically more than one movie, but it's a more satisfying answer than nothing). It was an amazing effort, and the result was probably about as successful as anyone could have hoped for. But I'm really a fan of the books. I can enjoy the movies, and that says a lot, but my loyalty is to the original.

Can you blame me? I started reading LOTR when I was in fourth grade and averaged something like 1.5 reps per year until I finished high school (including the Hobbit and the Silmarillion). I traced maps, charted family trees, practiced runes, and imagined myself in the stories for countless hours while mowing the lawn. Those books were the gold standard not only for their own story but for just about everything else I ever read.

Fortunately, I was not quite such a fanatic by the time the movies came out. I was much less obsessed, and I think in general I had matured to the point that I realized a movie must always distort the book on which it is based. To a great extent, I could accept the changes made. They ran upwards of three hours each, with extended DVD versions even longer, but there was still no way they could include everything. And some interactions just don't work on film like they do on paper. I get that.

I probably hadn't watched the movies since 2004, when the last one came out on DVD. Sitting down to watch just one of them without the others seems silly, and carving out enough time to watch all three extended versions (alone, because the kids weren't old enough, and Julie wasn't crazy enough) is no small task. But for a while I'd been thinking about just starting to watch in bits and pieces and eventually getting through. I finally started the other day, and of course it didn't happen like that. I watched roughly one full disc at a sitting and finished in less than a week.

I was surprised to find that, not only could I stomach most of the changes, but I actually had that tingling in the back of my head when the elvish contingent showed up for the battle of Helm's Deep. It's spurious but moving nonetheless.

But the Scouring of the Shire. Jackson not only ignored it--he threw it hurtling from the top of Orthanc to a grisly death below. (Don't feel bad for Saruman--he may not make it to the end of the movie, but he gets an inflated role earlier to make up for it.) The discovery of Longbottom Leaf is retained (at least in the extended version), but is reduced to mere nostalgia instead of the ominous sign that it is in the book.

You could chalk it up to mere length, but as I recall they explicitly stated their reasons, and a significant motivation was that it just seemed to drag out the story anyway. The war is over, so wrap things up and be done with it. But this time watching, I had an epiphany. (I'm sure many have seen it already, but I'm slow with these things.) The Scouring of the Shire (and its absence) has a lot to do with the context in which the story is written.

If you don't know, the Scouring of the Shire is the penultimate act of the story. After the war ends, Aragorn is crowned and married, and everyone travels back home, there remains the task of mending the hobbits' beloved Shire. It comes out that Saruman was deeply involved with that part of Middle Earth, and his henchmen were running things at the expense of the hobbits. The movies get his obsession with machinery and progress; in the books this obsession wrecks the agrarian Shire even after the war seems over. The four hobbits return, Saruman meets his end, and the cleanup process begins.

Tolkien wrote LOTR in the context of WWII. As in most of Europe, the war did not end for England when Berlin fell. There was physical damage to repair, and there were lasting political changes as a result of the war effort (many of which, I would guess, Tolkien also thought needed repair). War had changed the home front, even if its worst effects were elsewhere.

But in 21st c. America (and although Jackson is from New Zealand, I still think it's an American movie), wars don't affect us here at home. Sure, you might get the occasional raid by a Black Rider or two, but the real combat is safely contained somewhere else. Our lifestyle doesn't have to change (if it did, the terrorists would win), our economy doesn't change (well . . . ). War is someone else's problem. The only negative effect is when soldiers return with their scars and have trouble assimilating back into "normal" life. And the life they return to is hopelessly normal. So, instead of the Scouring, we get a scene of the four heroes sitting in the Green Dragon, exchanging knowing looks.

Of course the Scouring seems to drag out the story needlessly when viewed from our perspective. Having a ravaged home after returning from war seems like a superfluous and cruel addition, not a predictable consequence. Tolkien couldn't write his story without it, because it was the stark reality of war. Jackson couldn't write his story with it, because if our wars change anyone's life, it's certainly not ours.

Can you blame me? I started reading LOTR when I was in fourth grade and averaged something like 1.5 reps per year until I finished high school (including the Hobbit and the Silmarillion). I traced maps, charted family trees, practiced runes, and imagined myself in the stories for countless hours while mowing the lawn. Those books were the gold standard not only for their own story but for just about everything else I ever read.

Fortunately, I was not quite such a fanatic by the time the movies came out. I was much less obsessed, and I think in general I had matured to the point that I realized a movie must always distort the book on which it is based. To a great extent, I could accept the changes made. They ran upwards of three hours each, with extended DVD versions even longer, but there was still no way they could include everything. And some interactions just don't work on film like they do on paper. I get that.

I probably hadn't watched the movies since 2004, when the last one came out on DVD. Sitting down to watch just one of them without the others seems silly, and carving out enough time to watch all three extended versions (alone, because the kids weren't old enough, and Julie wasn't crazy enough) is no small task. But for a while I'd been thinking about just starting to watch in bits and pieces and eventually getting through. I finally started the other day, and of course it didn't happen like that. I watched roughly one full disc at a sitting and finished in less than a week.

I was surprised to find that, not only could I stomach most of the changes, but I actually had that tingling in the back of my head when the elvish contingent showed up for the battle of Helm's Deep. It's spurious but moving nonetheless.

But the Scouring of the Shire. Jackson not only ignored it--he threw it hurtling from the top of Orthanc to a grisly death below. (Don't feel bad for Saruman--he may not make it to the end of the movie, but he gets an inflated role earlier to make up for it.) The discovery of Longbottom Leaf is retained (at least in the extended version), but is reduced to mere nostalgia instead of the ominous sign that it is in the book.

You could chalk it up to mere length, but as I recall they explicitly stated their reasons, and a significant motivation was that it just seemed to drag out the story anyway. The war is over, so wrap things up and be done with it. But this time watching, I had an epiphany. (I'm sure many have seen it already, but I'm slow with these things.) The Scouring of the Shire (and its absence) has a lot to do with the context in which the story is written.

If you don't know, the Scouring of the Shire is the penultimate act of the story. After the war ends, Aragorn is crowned and married, and everyone travels back home, there remains the task of mending the hobbits' beloved Shire. It comes out that Saruman was deeply involved with that part of Middle Earth, and his henchmen were running things at the expense of the hobbits. The movies get his obsession with machinery and progress; in the books this obsession wrecks the agrarian Shire even after the war seems over. The four hobbits return, Saruman meets his end, and the cleanup process begins.

Tolkien wrote LOTR in the context of WWII. As in most of Europe, the war did not end for England when Berlin fell. There was physical damage to repair, and there were lasting political changes as a result of the war effort (many of which, I would guess, Tolkien also thought needed repair). War had changed the home front, even if its worst effects were elsewhere.

But in 21st c. America (and although Jackson is from New Zealand, I still think it's an American movie), wars don't affect us here at home. Sure, you might get the occasional raid by a Black Rider or two, but the real combat is safely contained somewhere else. Our lifestyle doesn't have to change (if it did, the terrorists would win), our economy doesn't change (well . . . ). War is someone else's problem. The only negative effect is when soldiers return with their scars and have trouble assimilating back into "normal" life. And the life they return to is hopelessly normal. So, instead of the Scouring, we get a scene of the four heroes sitting in the Green Dragon, exchanging knowing looks.

Of course the Scouring seems to drag out the story needlessly when viewed from our perspective. Having a ravaged home after returning from war seems like a superfluous and cruel addition, not a predictable consequence. Tolkien couldn't write his story without it, because it was the stark reality of war. Jackson couldn't write his story with it, because if our wars change anyone's life, it's certainly not ours.

Friday, April 2, 2010

Passion Gospels

I was curious about exactly how much material was covered in the twelve Passion Gospel readings. The passages are:

Even so, it should be expected that some of the material unique to Luke will be omitted, and that is in fact the case. Particularly, Luke's longer account of the walk to Golgotha is missing, and more notably, the entire hearing before Herod. The Synoptic account of Jesus's prayers in the Garden also fails to make the cut, but it does turn up in the composite reading from the preceding vespers.

The overall flow of the twelve readings is chronological, with a good deal of overlap:

I'm still a bit puzzled as to the omission of the hearing before Herod. Was it incidental, merely a by-product of the overall preference for John and Matthew? Or was it intentional, and if so, why? I'm probably just forgetting something, but I can't recall Herod being mentioned in the liturgical texts of Holy Week. That wouldn't necessarily explain the omission, but it would be consistent. Perhaps it was enough to show both the Jewish side and the Roman side in Jesus's death. Is Herod superfluous in that sense? He seems to have a unique perspective, being mostly interested in Jesus as a wonder-worker. It's an obsession that can preach, but perhaps in the overall message of Jesus's death, it's just not that important.

- John 13:31--18:1

- John 18:1-28

- Matt 26:57-75

- John 18:28--19:16

- Matt 27:3-32

- Mark 15:16-32

- Matt 27:33-54

- Luke 23:32-49

- John 19:25-37

- Mark 15:43-47

- John 19:38-42

- Matt 27:62-66

Even so, it should be expected that some of the material unique to Luke will be omitted, and that is in fact the case. Particularly, Luke's longer account of the walk to Golgotha is missing, and more notably, the entire hearing before Herod. The Synoptic account of Jesus's prayers in the Garden also fails to make the cut, but it does turn up in the composite reading from the preceding vespers.

The overall flow of the twelve readings is chronological, with a good deal of overlap:

- Johannine Last Supper teachings

- arrest, Jewish trial, denial (John)

- Jewish trial, denial (Matthew)

- Roman trial, mockery (John)

- Judas, Roman trial, mockery (Matthew)

- mockery, crucifixion (Mark)

- crucifixion, death (Matthew)

- crucifixion, death (Luke)

- crucifixion, death (John)

- burial (Mark)

- burial (John)

- guard (Matthew)

I'm still a bit puzzled as to the omission of the hearing before Herod. Was it incidental, merely a by-product of the overall preference for John and Matthew? Or was it intentional, and if so, why? I'm probably just forgetting something, but I can't recall Herod being mentioned in the liturgical texts of Holy Week. That wouldn't necessarily explain the omission, but it would be consistent. Perhaps it was enough to show both the Jewish side and the Roman side in Jesus's death. Is Herod superfluous in that sense? He seems to have a unique perspective, being mostly interested in Jesus as a wonder-worker. It's an obsession that can preach, but perhaps in the overall message of Jesus's death, it's just not that important.

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

my story (or a version thereof)

In a group that Julie and I meet with, we've been discussing "our stories." I've long held the conviction that such things are necessarily selective and fluid, and rarely told the same way twice. So even though I've written down my story before, it's never come out quite this way. Read it as much for what it says about me now as for what it may say about my past:

My governing sins have always been in the areas of pride and vainglory. I have generally been confident in my own intellectual abilities, at the expense of everything else. I think I believed in God from as early as I can remember, but I didn't really start to take my faith seriously until I reached sixth grade. From that point on, I found ways to serve pride through religion.

My Sunday School teacher decided to pay students money as an incentive to read the Bible. That kind of mercenary spirituality would continue into my teen years, with quiz team and a camp scholarship program that required things like reading and Scripture memory. I also began to make friends with men in the church who were older than my parents. As a general practice, this could probably be a good opportunity for spiritual influence on youth, but in my case I saw it as another recognition of intellectual maturity beyond my years. They got me hooked on Christian apologetics, which encouraged me to "share my faith" through argumentation. Throughout high school, it became my personal crusade to show others that Christians (namely, I) could be intellectually respectable.

From time to time adults, impressed with my abilities, would suggest that I become a pastor. At first I scorned the idea, thinking that my intellectual abilities were too great for professional ministry. I had chosen engineering as a career when I was in fourth grade, and I wasn't ready to give up the opportunity to remind people of that choice. I spiritualized it by identifying a calling in my intellect--I, as a smart guy, was best suited to influence other smart guys. Anything less would be a waste of the talent God had given me. But my pride was multifaceted, and it wasn't long before I found a way to make professional ministry serve its ends.

I suppose there is probably some positive use to the notion of ministry as a higher calling, but it's hard for me to see it as anything better than a lesser evil. Men--especially men with a personality to lead--will generally take pride in their career. If they're going to explain why they chose the path of ministry, it will need to be framed as a step above whatever else they could have done. Hearing enough of this sort of thing eventually had its effect on me, and one summer I finally decided to throw my symbolic stick in the fire and dedicate my life to whatever God wanted me to do. Conveniently, God still wanted me to show off my intellect, just in a different field. I made a deal with him at that point--if he would save me from the embarrassment of a weak public speaking ability, I would go to Bible college. At the time, I really did believe that God must have made the difference; now, I'm not so sure it wasn't just the force of my own determination to excel in a different area. Either way, my pride remained.

My pastor tried to advise me against Bible college. He suggested getting a bachelor's degree in some other field, then going to seminary. That way I would have a fall-back career if I needed to support myself, and I would get a higher-level ministry education. I figured school was mostly just a formality anyway--I could learn whatever I needed to, when I needed to--so I wanted to get through it as quickly as possible. Worrying about a fall-back career would just be a sign of weakness. At the same time, I did recognize something about my own tendencies. I was genuinely concerned that if I gave myself too much opportunity I might choose something more comfortable than ministry. But the advice he gave was wiser than I imagined at the time, and it was arrogant to write it off so quickly.

In college, my focus began to shift away from apologetics to the core areas I was studying--Bible and theology. No longer surrounded by unbelievers who needed to be convinced that Christianity was true or respectable, I got my thrills from arguing with classmates about mostly pointless theological controversies. I was attracted (even when I disagreed) to the most intellectual and controversial of professors, and when authority clashed with heresy, I chose the latter. Even so, I had absorbed the narrow focus of the fundamentalist college I was attending. I ended up going on to seminary after all, and I chose one that was comfortably similar in doctrine but intellectually more rigorous.

Even going to seminary was a last-minute decision. It was not my original plan, but as I neared the end of my undergraduate studies, I realized that I was too young for the kind of job I really wanted. Also, school was comfortable for me and held less uncertainty than ministry. Many of the same trends continued in seminary, as I gravitated toward the areas that would be most intellectually challenging, most obscure, most academic. Not surprisingly, I decided before I was done that I would rather teach than pursue pastoral ministry, which meant I would have to go on for a Ph.D. But there was a spiritual dimension to this shift that took me longer to recognize.

I don't think I ever really had much of a true devotional life. In youth group, I was expected to keep a journal of prayer and scriptural meditation. It was checked regularly for completeness, but not at a level that would distinguish real interaction with God from intellectual contemplation of the assigned passages and meticulous maintenance of prayer lists. From time to time, college and seminary classes also required me to keep some kind of devotional journal, and I would comply as necessary. But aside from that, I generally assumed that my school work was spiritual enough. Early on, I developed a methodology for what I was doing. If the goal was to know and serve God better, I needed to understand what he expected of me. To understand that, I needed to grasp biblical theology and praxis. To grasp that, I needed to read and analyze Scripture intelligently. To read and analyze, I needed to get as close to the original texts as I could. And so, my intellectual pursuits were organized around acquiring the tools I needed to do all of this for myself, not to rely on anyone else's conclusions. Assuming I was actually working toward that goal, it all should have added up to spiritual growth, without adding anything else to the mix.

In the same way that I had no real relationship with God, after marriage, I had no real relationship with my wife. Most of my time was devoted to school and work. Even when we were together in our apartment, we were usually doing different things. I did not concern myself with what she wanted or even needed, and I justified it all as a temporary condition that would stop when I was done with school. But school dragged on, and things didn't change.

I was required to serve in church during college and seminary, and so I did. I genuinely cared about doing well whatever I was given, and I honestly looked for ways to apply my abilities to the greatest use. But I don't think it was ever an expression of love for God or even for other people. It was preparation for my chosen career, and I naturally wanted to do it well. But eventually my intellectual pursuits began to outpace other aspects of my life. I sensed a widening gulf between what I thought and what I did. And I knew that there were limits to what I could say out loud or apply in real life. My eccentricity was accepted to a degree, but church life was insufficiently flexible to accommodate full disclosure. That's when I realized that I could not be in paid ministry, whether I wanted to or not, and I also realized that I wouldn't have much future teaching in the kind of schools I'd attended.

So by the time I started my Ph.D. program, I was back to looking at the secular arena for my career. I figured that if necessary a Ph.D. in Semitic languages could be applied in a seminary, but I was really interested in teaching in a secular or at least not-so-fundamentalist college or university, where no one would care exactly what I thought about conclusions, as long as I could teach the right methods. It would probably have been less costly in terms of time, money, energy, and relationships if I'd just decided to pursue a different career altogether. But I was trying to save face, to prove to myself and others that I had not wasted the past several years of my life on a career that I would never pursue.

The crux came when I finished coursework on my Ph.D. and simultaneously became a father. In my self-centered pursuit of academic goals, we had put off having kids as long as we could. But now I had more freedom with how I used my time and more motivation to get things right. I somehow sensed that real life was becoming considerably more important than academia, and I pushed school to the back burner, in favor of sorting out more practical issues like faith and politics. I was still self-centered, to be sure, but I think it was an important step to open up my closed, little world to the influences of reality. I concluded pretty readily that I could not continue down the same "spiritual" path--which, as I said, was never really all that spiritual in the first place. But now it was intellectually impossible, like trying to go back and watch a magic show after you've seen how the trick works. No force of will can make you believe again.

I had followed the path to its end and found that it didn't really lead anywhere. Moving forward would mean making my own path (and knowing it). The only option that retained hope was to back up and turn aside into something altogether different. But I had become so jaded that even this move felt like I was still deliberately charting my own course--like there was no God to be found at the end, only more disappointment. But I could hold out hope that I would never get far enough to find out. I began exploring other faith traditions, looking for something that I could "live with"--something I could respect as honest about itself as a tradition, and intellectually challenging enough to hold my interest. I hadn't really changed all that much--it was still about what would make me feel a certain way, and still without any expectation of a real encounter with a real God.

My first trial was characteristic. I explored Rabbinic Judaism mostly through reading, without opening up to anyone else about my interest. One significant change was that I was by this point pursuing something with a more spiritual dimension to it. So I spent a good deal of time trying out Jewish prayer. But I was still not prepared to follow any path of conversion that would require me to start over. Some things I could give up, but not my freedom to challenge the status quo.

I briefly considered Messianic Judaism as an alternative. It would not require a formal conversion, or a renunciation of anything in particular, and there was a better chance that my wife would go along with it. But it had too many of the same problems that had turned me off to Evangelicalism, in some cases to a greater degree. Ultimately, it was not a viable option, but this stage included some important turning points. One was that I finally opened up to my wife about what was going on. We were still miles apart on these things, but at least I was operating somewhat outside of my own head. Another was that it raised questions for me about early Christianity, which pointed me in the direction of Eastern Orthodoxy. It was a purely intellectual progression at the time, but I don't know how else I would have got there.